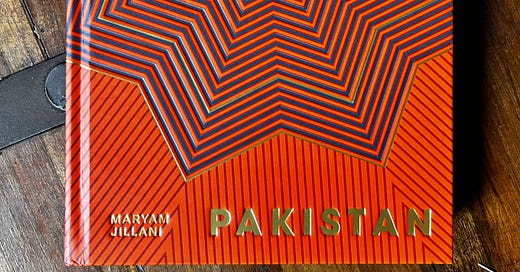

Leafing through a cookbook is, I think, one of life’s pleasures. From those that transport you to another place, provide a deep dive into a particular ingredient, an introduction to an alternative cooking method or just plain comfort, despite often sharing commonalities, there is nearly always something to be gleaned from a new cookbook. A few standouts…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apples & Elderflower to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.